And, this is the second review that has been sitting draft forever – it was originally published January 24, 2015.

Death in the Stocks

Death in the Stocksby Georgette Heyer

Series: Inspectors Hannasyde & Hemingway #1

Publication Date: July 1, 1935

Genre: mystery

Pages: 262

In the dead of the night, a man in an evening dress is found murdered, locked in the stocks on the village green. Unfortunately for Superintendent Hannasyde, the deceased is Andrew Vereker, a man hated by nearly everyone, especially his odd and unhelpful family members. The Verekers are as eccentric as they are corrupt, and it will take all Hannasyde's skill at detection to determine who's telling the truth, and who is pointing him in the wrong direction. The question is: who in this family is clever enough to get away with murder?

Heyer is better known for her romances than her mysteries, and for good reason, honestly. This was a reasonably entertaining mystery, but was really nothing special. It is very much a class-based mystery, as are many of the golden age mysteries.

The book begins with the grisly discovery of a body in the stocks in the village of Ashleigh Green – Arnold Vereker has been stabbed. Arnold is the wealthy eldest brother of the Vereker family, and the prime suspects are his two siblings: the smashing Antonia, who is engaged to Rudolph, and employee of Arnold’s and not a particularly suitable partner for Antonia, and Kenneth, the artistic freeloader who is engaged to the beautiful and expensive Violet. It’s obvious that Arnold has been murdered for his money. The question is which of the suspects, all of whom loathed Arnold, is the guilty party.

I get the sense that Heyer was a bit of a snob, mostly from reading biographical stuff about her, but also from her books. This mystery – along with the one other mystery I’ve read of hers – relies heavily on the “Bright Young Thing” trope that is common in golden age mysteries. The BYT is a young, generally extremely attractive, female character who is a bit bohemian, who always ends up marrying someone whom she will enliven, at the same time that he will steady her. She is sort of a precursor to the MPDG (manic pixie dream girl) character trope that we’ve seen more recently.

The BYT is always desirable, and is the “heroine” of the piece. She is usually attached to someone who is not good for her – as Tony was at the beginning of this story. Giles is the perfect foil for the BYT – he is steady, but not staid, and head-over-heels for the girl. He is a Mr. Knightley, as opposed to a Mr. Wickham or a Mr. Willoughby. Not interesting enough to carry the book on his own, he’s the classic nice guy who deserves to win the hand of the cool girl. As soon as Giles ends up in the same room with her, we KNOW that he is the guy for Tony.

Violet, on the other hand, is NOT a BYT. First of all, she’s not that bright. And she’s a gold-digger – she is not sufficiently light-hearted or bohemian. It isn’t Violet’s lower class roots, but her actual lack of class, that excludes her. Being a BYT wasn’t actually dependent on having money – it was all about attitude. One could sponge off others, but not be a gold-digger, as long as one was convincingly able to maintain the fiction that money was unimportant. I know this makes no sense, but this is the sense I make of the trope after reading tons of these books.

Ultimately, the relationship with money in books of this time period can be really conflicted (as it was for Heyer herself!). Having money is perceived as admirable, but making money is grubby and greedy. So, Tony & Kenneth could live off of Arnold’s labor, and still feel his superior because, you know, they didn’t care about money. Even though the money that allows them to eat comes directly from him. It’s schizophrenic at best, hypocritical at worst.

Unfortunately, this trope has not worn well in the modern era of rising inequality. I found Kenneth deplorable, and Tony annoying. I wanted them both to get off their underwhelming, overindulged asses and do something – anything – useful. Arnold was awful, but he was no more awful than the people around him. He might have even been less awful. At least he was capable of feeding himself.

Tying this back to Heyer, she was involved in a tremendous conflict with Inland Revenue during her lifetime. She wrote because it paid the bills, but was constantly fighting about taxes, and at one point set up a LLC to try to lessen her tax burden, then basically got caught treating the LLC like it was her bank account, and the tax authorities got pissed and told she owed a bunch of money. Which I believe she ultimately paid, but she was not happy about it. She, herself, was more like Arthur (probably) than like either Violet or Antonia/Kenneth, but I think that she clearly sympathized with “the gentry” and the “leisured class.”

Over all, this is a reasonably enjoyable golden age mystery, although I never find Heyer’s mysteries as well-plotted as Christie’s or as enjoyable and quirky as Sayers. She’s definitely a second tier mystery novelist. And all of the characters could have used a swift kick in the ass.

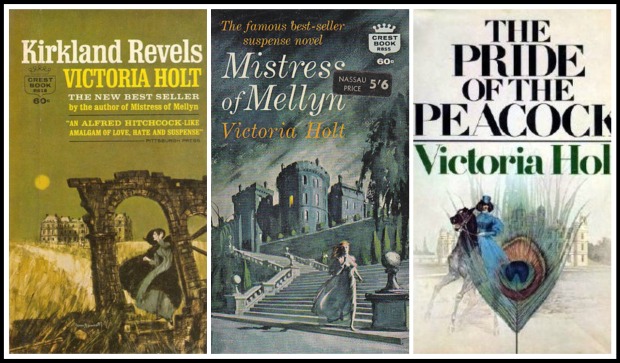

Mistress of Mellyn

Mistress of Mellyn

Lady of Quality

Lady of Quality Arabella

Arabella Bel Lamington

Bel Lamington Fletcher's End

Fletcher's End Powder and Patch

Powder and Patch

North and South

North and South

Nightingale Wood

Nightingale Wood Katherine Wentworth

Katherine Wentworth The Eternity Ring

The Eternity Ring