This is a very old review that was originally published on a different blog all the way back on October 26, 2014. It’s been sitting my draft reviews since I shut that blog down and copied it over. I decided that it was time to empty the draft folder of all of the really old stuff. There are only a couple that I decided to keep and publish here. This is one of them.

Mistress of Mellyn

Mistress of Mellynby Victoria Holt

Publication Date: January 1, 1960

Genre: gothic romance, romance

Pages: 240

Mount Mellyn stood as proud and magnificent as she had envisioned... But what about its master--Connan TreMellyn? Was Martha Leigh's new employer as romantic as his name sounded? As she approached the sprawling mansion towering above the cliffs of Cornwall, an odd chill of apprehension overcame her.

TreMellyn's young daugher, Alvean, proved as spoiled and difficult as the three governesses before Martha had discovered. But it was the girl's father whose cool, arrogant demeanor unleashed unfamiliar sensations and turmoil--even as whispers of past tragedy and present danger begin to insinuate themselves into Martha's life.

Powerless against her growing desire for the enigmatic Connan, she is drawn deeper into family secrets--as passion overpowers reason, sending her head and heart spinning. But though evil lurks in the shadows, so does love--and the freedom to find a golden promise forever...

There is basically a straight line from Jane Eyre to Rebecca by du Maurier, to Victoria Holt.

When I was just a girl, it was the 1970’s, a time of great change. The first wave of feminism – concerned with legal/structural barriers to inequality like suffrage and property rights – had largely ended, at least in the Western world, and the second-wave had begun. The second wave of feminism broadened the debate to other barriers to gender equality: sexuality, family, reproductive rights, education and the workplace.

I bring this up for a reason. And that reason is that Victoria Holt’s gothic romances were huge in the 1960’s and 1970’s, and the tropes which are present in those books are oddly anti-feminist. The Mistress of Mellyn, her first gothic romance, was published in 1960. In addition to the Mistress of Mellyn, I’ve also recently read The Bride of Pendorric (1963), The Shivering Sands (1969), and The Pride of the Peacock (1976). She published a total of 32 of these stand-alone gothics, with 18 of them being published in the 1960’s and 1970’s.

Do I think that Eleanor Hibbert, who wrote under the name Victoria Holt, was anti-feminist? No, absolutely not. She was an incredibly prolific writer who wrote under 8 separate pen names, including her most well-known: Jean Plaidy, Victoria Holt and Philippa Carr.

But with her Victoria Holt gothics, she tapped into something. She was not the only writer of gothic romance publishing during this time period. Other well-known writers include Phyllis Whitney, Dorothy Eden, Barbara Michaels, and Mary Stewart.

A few observations about gothic romance.

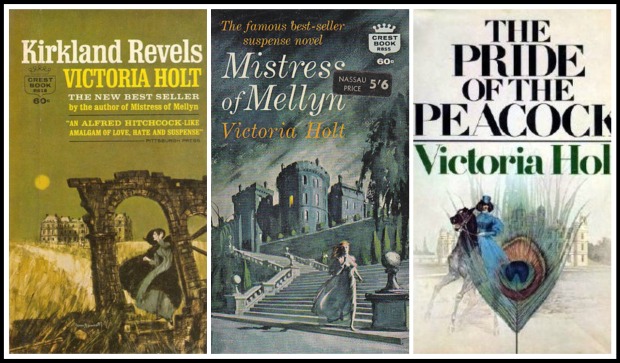

1. The covers were remarkably similar, typically featuring a castle or a manor of some sort, with a young woman running from it. Some examples:

2. The setting is of critical importance: it is typically a place that is both exotic but remains well-trod ground. Cornwall – the Cornwall of du Maurier and Rebecca – is a common setting, as are Yorkshire moors, which is familiar to readers through Jane Eyre and Wuthering Heights. The settings have a darkness to them. The setting is historical, and the story typically conforms to well-established gender norms of the historical time period.

3. The main character is always a young woman of small means and dependence, similar to the unnamed narrator in Rebecca. She is often a governess, or a companion to a much wealthier woman. Typically youthful, her most significant characteristic is her powerlessness. She is generally not particularly beautiful – beauty being a characteristic that affords a woman with power – nor wealthy. She can be a widow or a virgin, but she is never sexually autonomous, and she never has children.

4. The male lead is a man of stature. Sometimes he is a widower, the father of a child that she has been hired to educate. He is always a man of property and is always above her station. He is aspirational, but she does not aspire to him, always acknowledging to herself that, while she has fallen in love with him, she cannot have him.

5. And it is the property that is, generally, the key to the story, as evidenced by the covers and the titles. These books are an offshoot of the literature of the English Country House. As Jane Eyre was focused around Thornfield Hall and Rebecca had Manderley, a great manor house is the foundation upon which these books are built.

6. Finally, these books often have a female villain, which is the entire point of this discussion.

The suspense in these books is built around the young woman coming to the manor house and falling in love with the eligible lord of the manor. Often there is a mystery associated with the man, or the house. A former wife who has disappeared, or a suggestion of murder, that places the heroine in physical danger. We are always meant to believe that it is the man who is the source of the danger.

However, that is typically not the case. There is confusion about the source of the danger, and the reason for that confusion is: the villain is a woman who is committing the villainy because of some ambitions either toward the master, or, more commonly, the house itself.

This is why I titled this post the corrosive effect of female ambition. Because in these books – at least the ones I have read recently – female ambition isn’t merely unwomanly, it is positively corruptive. It causes the woman who experiences it to devolve into a deranged murderess.

The Mistress of Mellyn is a case in point (and here, spoilers will abound). Our heroine is a Martha Leigh, a young woman who comes to Mount Mellyn as governess to Alvean TreMellyn, putative daughter of Connan TreMellyn (although we find out early on in the story that Alvean is actually the daughter of Alice’s lover, the neighbor). Connan himself is a widower, his deceased wife Alice having died in a railroad accident on the very night that she left him for his neighbor, her body so badly burned that it could only be identified by the locket she wore.

Drama ensues, and the reader begins to believe that there is something bizarre going on with the manor house. There are ghostly sightings, and a mute sprite of a child who seems to be terribly frightened for reasons which are unclear. The home itself is full of nooks and crannies and secret chambers, along with peeps that are cleverly hidden in murals so that the individuals in one room won’t know that they are being watched from another room.

As in many of these books, it turns out that the villainess is a woman: the sister of the neighboring man whom Alice was thought to have run away with and who died in the railroad accident. When Martha marries Connan, she becomes the target of the murderer, and is lured into a secret chamber, where she will be left to die, as was Alice so many years prior. The murderess is foiled by the child that Martha has befriended.

But, here is the thing. Celestine Nansellick isn’t actually interested in Connan TreMellyn. This isn’t a story of female rejection which ends with the rejected removing the victorious competition from the picture. This is all about the house – Celestine Nansellick covets Mount Mellyn, not Connan TreMellyn, and Martha gets in the way of those ambitions by marrying Connan and potentially producing legitimate heirs which will disinherit Alvean who is not Connan’s child. She wants the house, not the guy.

This is the same motive behind the murder attempt in Pride of the Peacock (deranged female housekeeper who wanted the aspirational hero to marry her daughter) and The Shivering Sands (deranged daughter of the housekeeper who believed herself to be the illegitimate child of the heir of the estate). In each of these books, the villain is a mirror image of the heroine, with one distortion – unlike the heroine, who is not ambitious and who accepts her place, the villain is prepared to dogfight her way out of subservience. She cannot marry her way out – unlike the heroine – but she can manipulate and maneuver and even murder her way out. And it is her very refusal to accept her place that marks her as unworthy of elevation.

This is completely retrograde, right? This book is published at the exact same time that women are becoming increasingly independent, able to control their own fertility, plan their families, get the same education as men, qualify for the same jobs, and yet we have a wildly popular type of book in which the heroines accept their lack of equality, and the villains reject it. And the women who reject this lack of independence and autonomy become criminals – murderesses.

The Landower Legacy

The Landower Legacy The Secret Woman

The Secret Woman